Generic Types Traits and Lifetimes

The notes reflect the topics in Chapter 9

Generic Data Types

C++ template, but no metaprogramming, with type checks, so we don’t see that endeless error message from C++ templates.

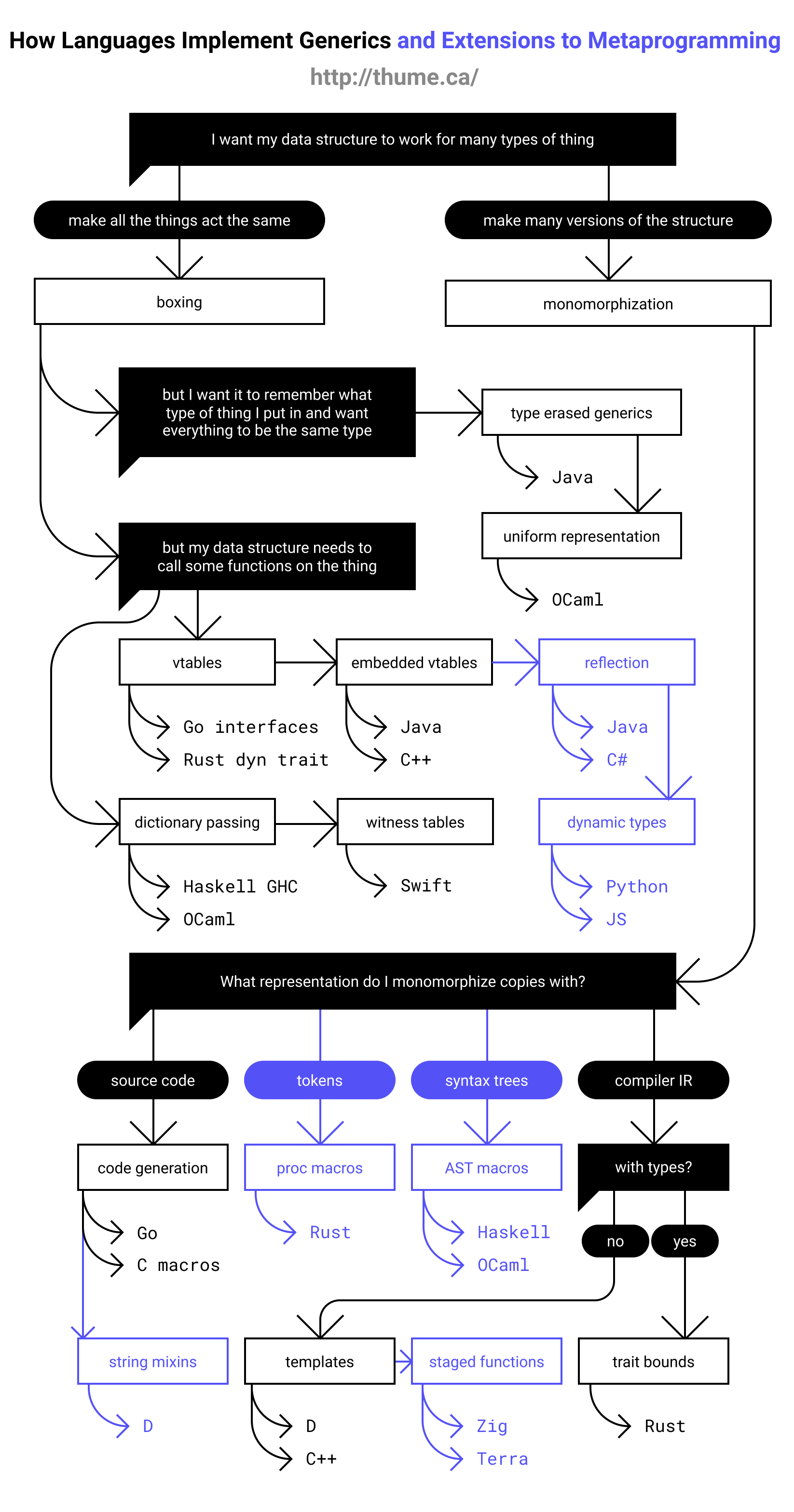

For a nice overview of how different languages handles this “generic” idea, see

this blog post.

Here’s a image in it:

struct Point<T> {

x: T,

y: T,

}

impl<T> Point<T> { // (1)

fn x(&self) -> &T { // (2)

&self.x

}

}

fn main() {

let p = Point { x: 5, y: 10 };

println!("p.x = {}", p.x());

}

-

The

There afterimplandPointare usually the same, except when we need to specify some traits. -

We can specify extra generic types for the method. e.g.

struct Point<T, U> { x: T, y: U, } impl<T, U> Point<T, U> { fn mixup<V, W>(self, other: Point<V, W>) -> Point<T, W> { // (1) Point { x: self.x, y: other.y, } } } fn main() { let p1 = Point { x: 5, y: 10.4 }; let p2 = Point { x: "Hello", y: 'c' }; let p3 = p1.mixup(p2); println!("p3.x = {}, p3.y = {}", p3.x, p3.y); }- The

V, Where are the extra types just for this method.

- The

For using generic types in function argument, we may need to specify its trait.

Traits

Traits is Rust’s way of doing ABC (in Python), or function overloading / single dispatch in C++. It provides a magic-like monkey-patching experience. I can add method to the object not owned by me by implementing trait, for them.

Here’s some sampling from Abstraction without overhead: traits in Rust of Rust blog:

- Traits are Rust’s sole notion of interface. A trait can be implemented by multiple types, and in fact new traits can provide implementations for existing types. On the flip side, when you want to abstract over an unknown type, traits are how you specify the few concrete things you need to know about that type.

- Traits can be statically dispatched. Like C++ templates, you can have the compiler generate a separate copy of an abstraction for each way it is instantiated. This comes back to the C++ mantra of “What you do use, you couldn’t hand code any better” — the abstraction ends up completely erased.

- Traits can be dynamically dispatched. Sometimes you really do need an indirection, and so it doesn’t make sense to “erase” an abstraction at runtime. The same notion of interface — the trait — can also be used when you want to dispatch at runtime.

- Traits solve a variety of additional problems beyond simple abstraction. They are used as “markers” for types, They can be used to define “extension methods” — that is, to add methods to an externally-defined type. They largely obviate the need for traditional method overloading. And they provide a simple scheme for operator overloading.

// Define the trait.

pub trait Summary {

fn summarize(&self) -> String;

// It can also have a default implementation (1)

// It can also call other code, just like ABC (2)

}

// Implement traints for our data structure.

pub struct NewsArticle {

pub headline: String,

pub location: String,

pub author: String,

pub content: String,

}

impl Summary for NewsArticle {

fn summarize(&self) -> String {

format!("{}, by {} ({})", self.headline, self.author, self.location)

}

}

pub struct Tweet {

pub username: String,

pub content: String,

pub reply: bool,

pub retweet: bool,

}

impl Summary for Tweet {

fn summarize(&self) -> String {

format!("{}: {}", self.username, self.content)

}

}

// Call it.

fn main() {

let tweet = Tweet {

username: String::from("horse_ebooks"),

content: String::from(

"of course, as you probably already know, people",

),

reply: false,

retweet: false,

};

println!("1 new tweet: {}", tweet.summarize());

}-

Like this

pub trait Summary { fn summarize(&self) -> String { String::from("(Read more...)") } } -

Like this

pub trait Summary { fn summarize_author(&self) -> String; fn summarize(&self) -> String { format!("(Read more from {}...)", self.summarize_author()) } }

When using traits in parameters…

pub fn notify(item: &impl Summary) {

println!("Breaking news! {}", item.summarize());

}

// That is same as

pub fn notify<T: Summary>(item: &T) {

println!("Breaking news! {}", item.summarize());

}

// It can specify multiple trait bounds

pub fn notify(item: &(impl Summary + Display)) {

println!("Breaking news! {}", item.summarize());

}

// More syntax sugar with where clause:

fn some_function<T, U>(t: &T, u: &U) -> i32

where T: Display + Clone,

U: Clone + Debug

{}

// Return type can be trait too.

fn returns_summarizable() -> impl Summary {...}

We can also conditionally implement method based on trait, just like

std::enable_if.

Lifetimes

Lifetime is Rust’s way of battling the following C++ code, without involving shared pointer, etc.:

// The class can only be created by Foo, and is valid as long as the Foo object that creates it is valid.

class FooView {

std::vector<Bar> &bar;

//...

}

The core issue here is that we need to somehow know the lifetime of the returned object (w.r.t. the input parameters). Since this information may be impossible to get in compile time, Rust ask us to provide it ourselves.

fn main() {

let string1 = String::from("abcd");

let string2 = "xyz";

let result = longest(string1.as_str(), string2);

println!("The longest string is {}", result);

}

fn longest<'a>(x: &'a str, y: &'a str) -> &'a str { // (1)

if x.len() > y.len() {

x

} else {

y

}

}

// Not used

struct ImportantExcerpt<'a> {

part: &'a str,

}

- The concrete lifetime that is substituted for

'ais the part of the scope ofxthat overlaps with the scope ofy. In other words, the generic lifetime'awill get the concrete lifetime that is equal to the smaller of the lifetimes ofxandy.

Lifetime Elision

Just some syntax sugar so you don’t need to write lifetime annotation every time. Note that this is not the same as C++ reference lifetime extension, which is another beast.

??? note “More on C++ reference lifetime extension”

So the rule basically states you are allowed to write code like

`const auto &foo = bar()`. And that `foo` just points so some magic location on

stack, basically extending the lifetime of the temp variable. More discussion

can be seen at

[Abseil Tip of the Week #107: Reference Lifetime Extension](https://abseil.io/tips/107)

and

[Abseil Tip of the Week #101: Return Values, References, and Lifetimes](https://abseil.io/tips/101).

For why do we even need this thing, see

[this StackOverflow question](https://stackoverflow.com/questions/39718268/why-do-const-references-extend-the-lifetime-of-rvalues).

TL;DR is that it's niche now that we have RVO.

Rust compiler, in the current state, use the following three rules to see if it can deduce the lifetime of all the things (note that it could be wrong):

- Each parameter that is a reference gets its own lifetime parameter. In other words, a function with one parameter gets one lifetime parameter: fn foo<‘a>(x: &‘a i32); a function with two parameters gets two separate lifetime parameters: fn foo<‘a, ‘b>(x: &‘a i32, y: &‘b i32); and so on.

- If there is exactly one input lifetime parameter, that lifetime is assigned to all output lifetime parameters: fn foo<‘a>(x: &‘a i32) → &‘a i32.

- If there are multiple input lifetime parameters, but one of them is &self or &mut self because this is a method, the lifetime of self is assigned to all output lifetime parameters. This third rule makes methods much nicer to read and write because fewer symbols are necessary

Static lifetime can be specified via

let s: &'static str = "I have a static lifetime.";.

Final Example

fn main() {

let string1 = String::from("abcd");

let string2 = "xyz";

let result = longest_with_an_announcement(

string1.as_str(),

string2,

"Today is someone's birthday!",

);

println!("The longest string is {}", result);

}

use std::fmt::Display;

fn longest_with_an_announcement<'a, T>(

x: &'a str,

y: &'a str,

ann: T,

) -> &'a str

where

T: Display,

{

println!("Announcement! {}", ann);

if x.len() > y.len() {

x

} else {

y

}

}